Description & Adaptation

Soybeans are a globally important oilseed crop, originally grown in China. They are warm-season plants and are in the legume family. Soybeans are used to produce oil for human consumption, specialty snacks and sauces, and high-protein meal for animal diets. While traditionally grown in warmer eco-zones, breeding efforts have yielded soybean varieties adapted to grow in more northern climates, including Saskatchewan.

Soybeans are sensitive to day length, which controls their growth and reproduction. As daylight hours wane later in the summer, the crop is signalled to start flowering. Growth stages are also heavily influenced by heat, with warmer temperatures hastening flowering and cooler temperatures delaying it.

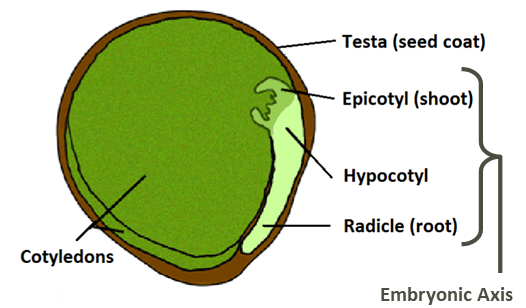

Soybeans exhibit epigeal germination, where the growing points emerge aboveground first. Soybean cotyledons are pretty large, so crusted soils can impede emergence. Higher seeding rates can help the plants push through the crusted topsoil together.

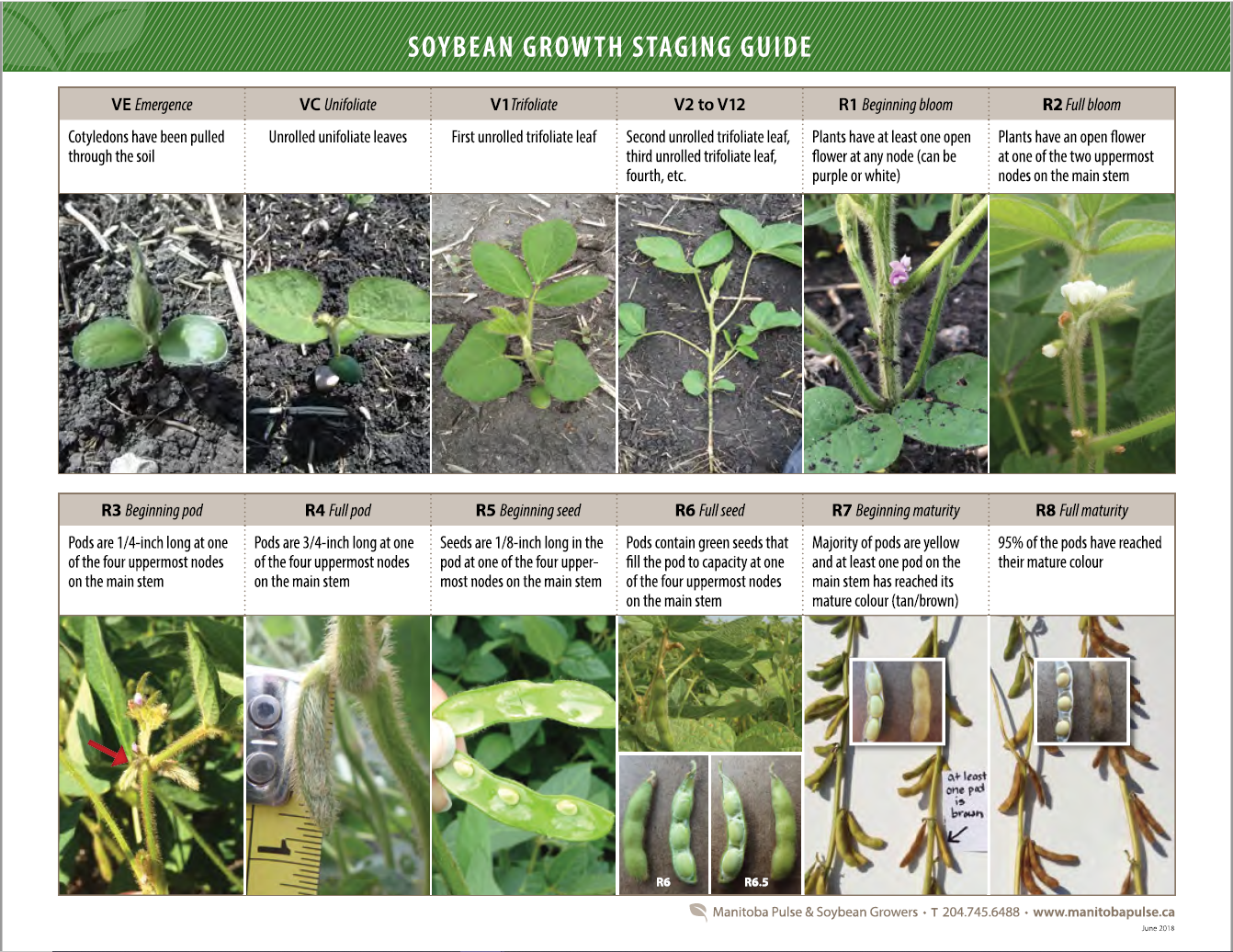

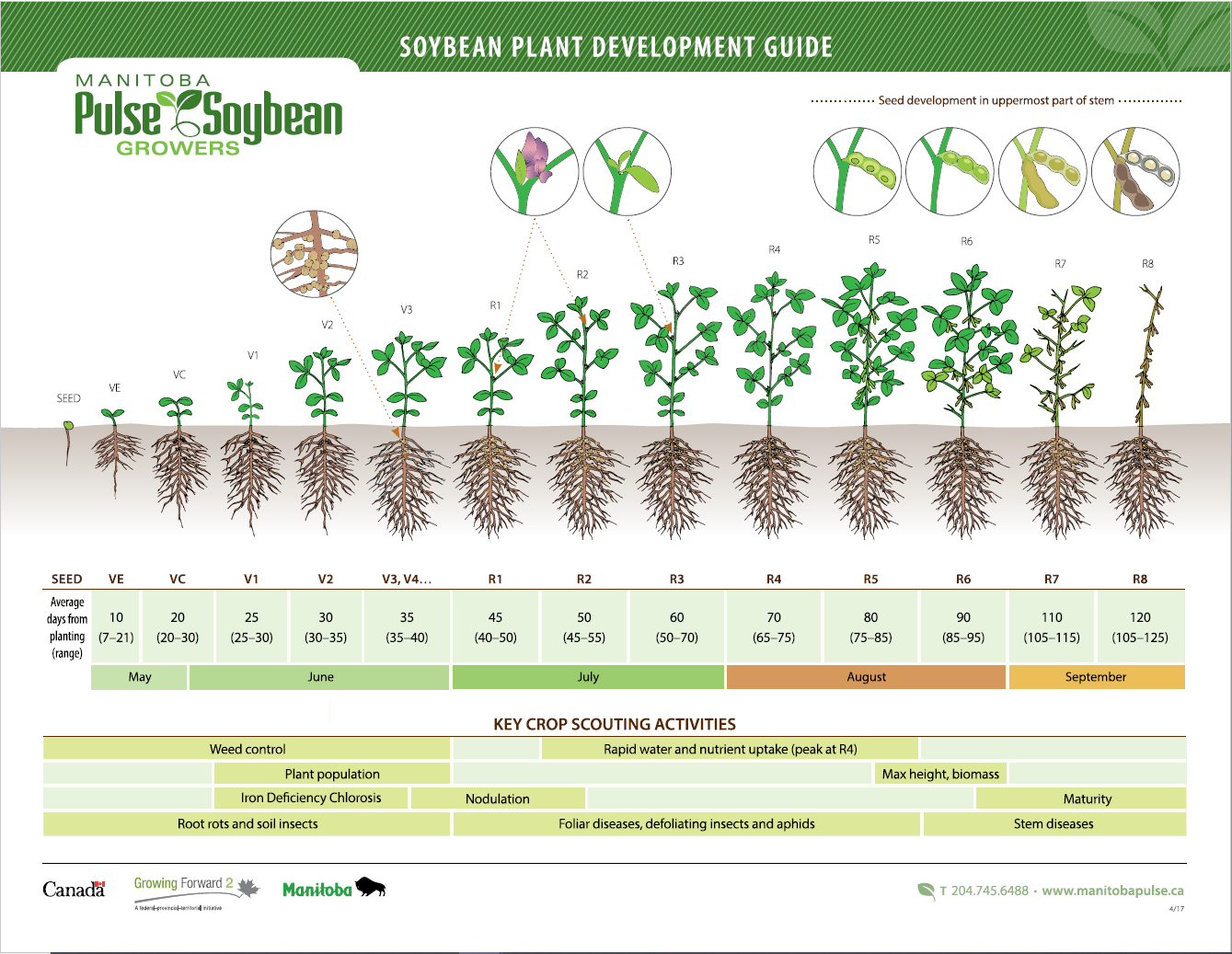

Soybean growth stages are divided into vegetative (V) and reproductive (R) stages. The first true leaves of the soybean plant are unifoliate with short petioles (known as the VC stage). Subsequent true leaves are trifoliate with long petioles, and are arranged alternately from side to side up the stem. New vegetative stages are reached about every five days from VC through V5, and every three days from V5 to shortly after R5, when the maximum number of nodes is reached. The plant will take approximately four to five weeks to form all of its nodes.

The reproductive stage begins (R1) when the crop starts developing buds. There is some overlap between the vegetative stages and the reproductive stages: soybeans enter the R1 stage during the V7 to V10 stage. Flowering peaks at the R2 or R3 stage (approximately six to eight weeks post-emergence), starting on the lower nodes and moving up the plant. Flowering typically concludes by R5. Flowers are purple or white and are self-pollinated. Warm temperatures accelerate development, especially flowering. Flowering may occur earlier with warm temperatures, but maturity may not necessarily be earlier because of day-length controls. Generally, yield increases as the length of the flowering-to-maturity stage increases.

Pods begin developing by the R3 stage, and it is not uncommon to find developing pods, withering flowers, open flowers, and flower buds all present simultaneously. Pods continue to build through R4, marking the beginning of the most crucial period for seed yield. Any stress (such as moisture, light, nutrient deficiencies, frost, or defoliation) between R4 and R6 will reduce yields more than at any other time. This is because at the R5 stage, flowering is complete, so new flowers will no longer develop to compensate for loss. During this time, plants also achieve their peak height and leaf area.

Soybeans are legumes and thus fixate a significant portion of the nitrogen they require from the atmosphere. Active nitrogen fixation begins around the V2–V3 stages, with developing nodules observed soon after emergence, peaking between R4 and R6.

Maturity begins at R6, after the seed stage is complete. The leaves start to yellow and eventually fall off by R7 and R8. Soybeans are physiologically mature by the R7 stage, even with a few green pods remaining. Stress at this stage and beyond has little to no effect on yield.

Soybeans are best suited to loamy soils but may perform well on clay soils if conditions are favourable for rapid seedling emergence. Soybeans are sensitive to drought, so sandy soils may not have enough late-season moisture for good yields.

Production in Saskatchewan has shifted northward and westward as shorter-season varieties are introduced. The southwestern area of the province, though warm enough, is typically too dry to meet the crop’s moisture requirements. Soybeans require between 450 and 750 millimetres (mm) of moisture per season, depending on the climate and length of the growing period. They need a substantial portion of this during the critical flowering and pod-fill period, which occurs in late July and August. If drought conditions occur during the crucial period, yields may be reduced. Since soybeans are photosensitive and latitude significantly affects day length, varieties are bred for specific north-south adaptation ranges, typically 150 to 250 km. Growing a variety south of its maturity band may result in earlier maturity and reduced yield; likewise, growing a variety north of its maturity band may delay maturity and risk not reaching full maturity before frost.

Related Resources

Varieties

Variety selection is one of the most critical factors in achieving high yields. In Saskatchewan, soybean maturity is one of the most important things to consider when selecting a variety. Additional factors to consider include yield potential and disease resistance.

Maturity is affected by growing conditions. If maturity is delayed into the fall, differences in maturity can be exaggerated as the days are shorter and temperatures are cooler. In warm, dry years, days-to-maturity may be fewer, and in cool, wet years, days-to-maturity may be greater. Growers need to understand which varieties perform well in their area and how their maturity compares with that of other varieties on the market.

Understanding Soybean Maturity Ratings

Soybeans are classified into maturity groups based on the relative maturity of comparative varieties. Maturity group values serve as a guide based on average conditions, providing a relative comparison for crops and varieties grown under similar conditions.

The maturity group (MG) rating system classifies soybean varieties from MG 000 in northern areas to MG IX in southern regions of North America, based on latitude ranges and photoperiod (daylight) sensitivity. Each MG region covers one or two degrees of latitude, or approximately 200 km from north to south. For Saskatchewan, the most suitable soybeans are those with MG 00 and 000. Each MG can have subgroupings numbered from one to nine following the group number. These decimal places equate to slight increases in maturity. In the 00 maturity ratings, a subgroup of 00.1 would be earlier maturing than 00.9. The respective company assigns these MG ratings based on comparison to current commercial varieties, and as a result, MG ratings are not entirely standardized between seed companies.

Related Resources

Seeding

Seeding Equipment

Soybeans can be seeded using conventional air drills and air seeders found on most farms. They can also be seeded as row crops with planters on row spacings ranging from 15 to 30 inches (38.1 to 76.2 cm). Research in Manitoba and North Dakota has found that narrow-row spacings typically yield the same or higher yields than wide-row spacings in Saskatchewan.

Narrow rows require slightly higher seeding rates than wider rows seeded with a planter to compensate for less concentrated spacing and potential seed damage, especially when the seed is less than 12% moisture. However, narrower rows will achieve canopy closure more quickly, reducing weed competition and conserving moisture.

Planting Date

Planting date is mainly determined by soil temperature because soybeans are susceptible to cold water uptake immediately after planting. Ideal soil temperatures are >10°C at seeding depth. Seeding below these temperatures may delay emergence and reduce stand establishment. The first water that the soybean absorbs in the hours after it is seeded should be warm to avoid seed chilling.

To reduce imbibition of cold water, soybeans should be seeded later in the morning, when soils have started to warm up from overnight lows, and avoid seeding if significant rain is forecast. Seeding as early as soil temperatures permit is essential, as late seeded crops can be more at risk of frost damage, and can have lower plant heights and lower pod establishment, making harvest difficult. May 10 to 25 is a typical seeding window for soybeans.

Once soybeans emerge, they can tolerate light frosts of up to -2°C for short periods, if the growing points are not damaged.

Seeding Rate

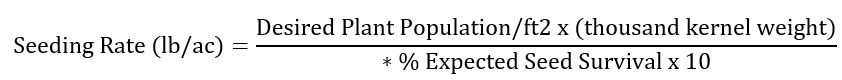

Soybean seeding rates should be determined by targeting desired final plant stands. Using this method, you need to consider the desired plant population, the variety’s seed size (thousand-kernel weight), and the percentage of seed survival. Soybean seeding rates are typically expressed in seeds per acre (seeds/ac).

The ideal final plant population ranges from 150,000 to 200,000 plants/ac (four to five plants per square foot). Seed survivability depends on equipment, seed quality, and seedbed conditions. A seed survivability of around 75% is typically achieved when using a drill, while a planter usually has a higher seed survivability rate. Seeding rates generally range from 70 to 140 pounds per acre (lb/ac). Exceeding ideal plant stand numbers can result in drought stress during dry years and lodging in wet years. Soybeans can branch to help compensate for lower plant stands, but plant height and pod height are usually lower with a less dense stand, creating harvestability challenges.

To determine the ideal seeding rate, the following formula can be used:

To convert seed per acre to lb/ac, divide the target plant population by the number of seeds per pound on the seed tag (ex. 209,150/2,600 seeds per pound = 80 lb/ac.

Seeding Depth

Soybeans are a relatively large seed and require adequate moisture to hydrate and germinate. Ideal seeding depths range from 0.75 to 1.5 in (1.9 to 3.81 centimetres). Deep-seeding can reduce emergence and increase the risk of disease infection from soil-borne pathogens.

Rolling Soybeans

Soybeans are harvested very low to the ground, so rolling should be done if possible. Soybeans are sensitive to rolling once they break the soil surface; therefore, it is essential to roll the field before emergence. If the pre-emergence window is missed, wait until the soybeans reach the first trifoliate stage. It should be a warm, sunny day, as this will cause the plants to wilt and be less likely to break.

Care should also be taken to avoid rolling when the soil is wet. Compaction and soil crusting can inhibit seedling emergence, especially in heavier-textured clay soils.

Seed Treatments

Soybeans are susceptible to several early-season seed and seedling diseases, as well as certain soil insects. Fungicide and insecticide seed treatments are available and should be assessed on a field-by-field basis.

Related Resources

display on the closing card of the video, with very limited characters. I want to be able to say that SPG funds root rot research in Saskatchewan. Can you help draft some text?

Inoculation & Fertility

Soybeans are a legume crop and can fix 50–60% or more of their required nitrogen. While they need more nitrogen to maximize yield than what is provided by fixation, it is not practical to apply additional nitrogen as fertilizer, as it can be antagonistic in the development of the fixation relationship and seldom results in increased yields. The bacteria Bradyrhizobium japonicum are not native to Saskatchewan soils, and soybeans must be inoculated. Inoculants are available in liquid, powder, and granular form.

In fields where soybeans have not been grown previously, double inoculation is recommended. Typically, double inoculation consists of a seed-applied liquid and an in-furrow granular inoculant. Check with your seed supplier, as some companies supply seed with a liquid inoculant already applied, so only a granular inoculant is required at seeding. When using seed treatments, the compatibility of seed treatments and inoculants should be confirmed, especially when applying liquid inoculants directly to the seed.

The number of nodules formed and the amount of nitrogen fixed increase with time until midway between reproductive stages (R5 and R6). Nodulation should be assessed at R1 or earlier, and you should find healthy nodules on each plant. Nodules are actively fixing nitrogen when they are pink when sliced in half. If no nodules are present and the crop appears yellowish-green, a rescue application of nitrogen should be considered at R2 (full flower) to R3 (early pod). Rescue treatments can be broadcast using granular or liquid nitrogen and are suitable if nitrogen is directed below the canopy to the soil surface and rainfall is imminent.

Soybeans are highly effective at extracting phosphorus from the soil, allowing them to be grown on fields with varying phosphorus levels. On high-phosphorus soils, there is often no response to additional phosphorus fertilizer. However, soybeans will remove approximately 0.85 lb of phosphorus pentoxide (P205) per bushel in the harvested seed, and crop rotations should be planned to maintain soil phosphorus levels in the range of 10 to 20 parts per million (ppm). When applying phosphorus with the seed, the maximum safe seed application rate of P205 is 10 lb/ac for wider rows or up to 20 lb/ac for narrower rows, provided there is good soil moisture and 15% seedbed utilization.

Uptake and removal of potassium by soybeans is higher than that of many other annual crops. Ideally, soybeans should be grown on soils with medium to high potassium levels, typically above 200 lb/ac. They will remove 1.4 lb of potassium oxide (K20) per bushel, and soil levels should be monitored to ensure depletion does not occur. If soil test levels are below 200 lb/ac (or 100 ppm), potassium fertilizer should be applied. Due to its toxicity, it should be used away from the seed.

Sulphur is another essential nutrient for soybeans. Soils with medium to high sulphur availability are ideal (>30 lb/ac). If sulphur is applied in rotation on a field with other crops (such as canola), there is usually enough for soybeans, so it should not need to be added. If grown on coarse-textured soils with low organic matter, a sulphur application may be beneficial. Removal of sulphur in the seed is 0.2 pounds per bushel (lb/bu).

While most Prairie soils contain adequate iron to meet the demands of growing soybeans, certain environmental conditions can reduce iron availability and uptake. If iron uptake is inadequate, a condition known as Iron Deficiency Chlorosis (IDC) results. Soil properties, environmental conditions, and variety susceptibility all affect the potential and severity of IDC.

Excess moisture, salinity, carbonates, and/or high nitrate levels in the soil can reduce the soybean’s ability to access iron. Higher pH soils (> 7.4) and saline soils are at a higher risk.

In saturated soils, IDC is often temporary and resolves as the soil dries out. If symptoms persist for longer than one week, yield loss can occur. There are no in-season management options; however, an accurate diagnosis can help adjust management in future years. If fields planned for soybeans are at risk of IDC, choosing a variety with a low IDC rating is essential. Varietal reactions to IDC (ratings 1 to 5) are available on the soybean varieties. Other management practices include improved drainage, higher seeding rates, and practices that reduce soil nitrogen levels. Iron chelate products applied in-furrow can reduce IDC, but susceptible varieties may still result in yield loss.

Soybeans exhibiting visual signs of IDC show yellowing of new leaves between the veins and an overall yellowing of the field, especially during the early vegetative stage in June.