By Chuck Penner, LeftField Commodity Research

April 2025

Normally, farmers’ planting decisions are largely locked in early in the planning cycle as crop rotations dictate most of the acreage. Sure, there are often a few “swing acres” that can change closer to seeding but it is a small percentage of the total. This means a Statistics Canada (StatCan) acreage survey conducted in mid-December to mid-January can usually provide a reasonable look at farmers’ decisions closer to spring.

But as we have seen, this is hardly a normal year. Uncertainty about United States (U.S.) import tariffs has swirled around for a few months with on-again off-again announcements. Indian tariffs on lentils and possible tariffs on peas are also part of the outlook. These developments will not be good for farmers’ returns but are not coming as a complete surprise. In contrast, Chinese tariffs on peas and canola products came completely out of the blue and the magnitude of this shock is causing more farmers to reevaluate planting decisions.

If there is any positive aspect in all this trade turmoil, it is that it is occurring before the crop is in the ground and allows the opportunity to make changes to the crop mix. That said, this chaotic situation aggravates issues with StatCan’s results from its early acreage survey. Even so, the numbers can serve as a starting point from which to make adjustments.

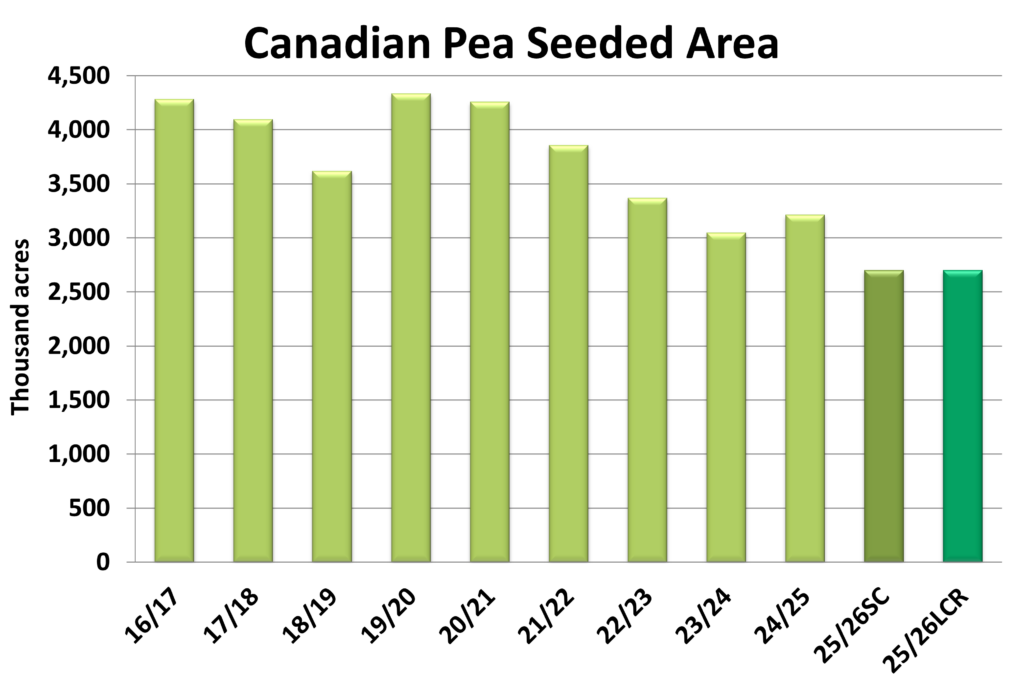

StatCan’s early survey results showed 2025 pea seeded area at 3.52 million acres, almost 10% higher than last year and the most since 2021/22. That may have been valid a few months ago when yellow pea prices were still solid and green and maple pea prices were rallying to multiyear highs, but things have changed. Indian import tariffs on peas are still a possibility while U.S. tariffs would have a smaller negative impact on demand. More significantly, the pea market was turned on its head when China imposed 100% tariffs on all classes of pea imports from Canada.

The potential for Indian and U.S. tariffs on peas may have discouraged some plantings in the months since StatCan’s survey, but the more recent shock of the Chinese ruling means farmers will likely be reducing acreage in a bigger way. There is no way of knowing exactly how many farmers are making late changes, but a 500,000 acre (16%) acreage drop from the 3.2 million acres in 2024 would not be unreasonable.

For the 2025/26 outlook, the size of the Canadian pea crop will be less of an issue than the amount of demand from key importers. Under the worst-case scenario, where all three countries impose tariffs, even a large acreage drop would still result in heavy pea supplies. On the other hand, an optimistic outlook in which China relents on its import tariffs and India and the U.S. hold off on tariffs would mean that fewer acres could trigger a supply shortfall.

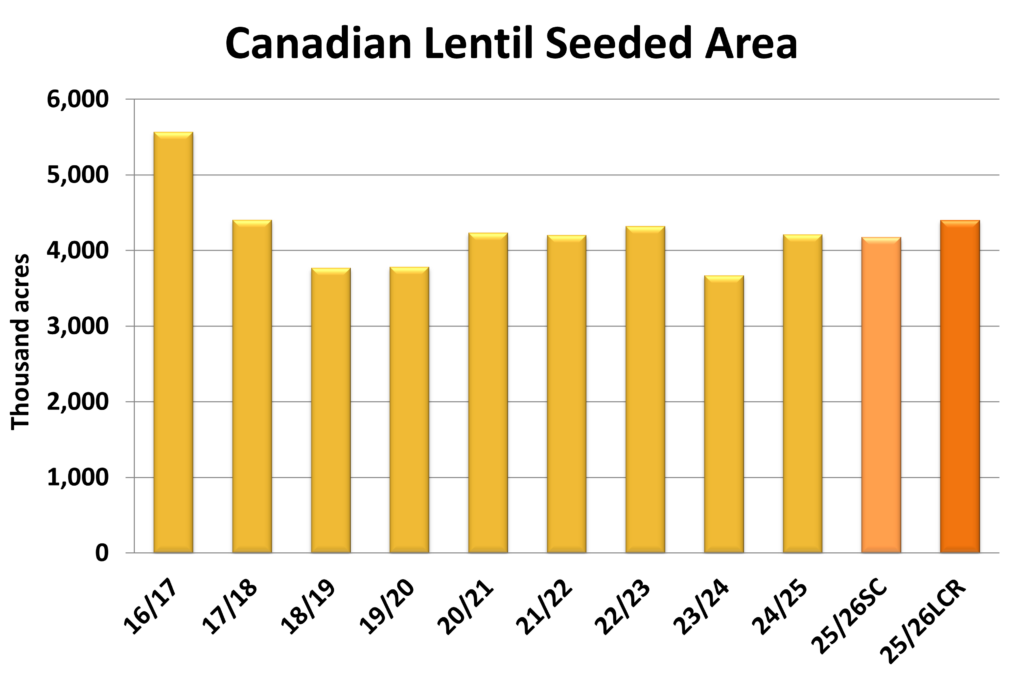

It is a sign of the scale of the latest current market chaos that India’s recent 11% tariffs on lentil imports seem to be a minor irritation rather than a crisis. That said, India’s decision to reimpose tariffs on lentils has caused a noticeable downturn in red and green lentil prices in Western Canada. If there is anything positive, it is that the tariff is not large enough to shut down trade. But it does make it more costly for Canadian farmers.

Because the Indian tariffs are a hurdle but not an insurmountable barrier, they’re likely having less impact on farmers’ planting decisions. StatCan’s estimate of lentil seeded area came in at 4.17 million acres, down less than 1% from a year ago and that appears reasonable. That said, the spillover from the pea market chaos could cause a few of those acres to shift to lentils, as farmers look to keep a pulse crop in their rotations.

Seeded area of lentils has been quite stable in the past number of years, hovering on either side of 4 million acres and another modest change in 2025 will not likely rock the boat too much. As always, export demand is critical but volumes to India won’t likely be affected significantly by an 11% tariff and the U.S. is not a large market for Canadian lentils.

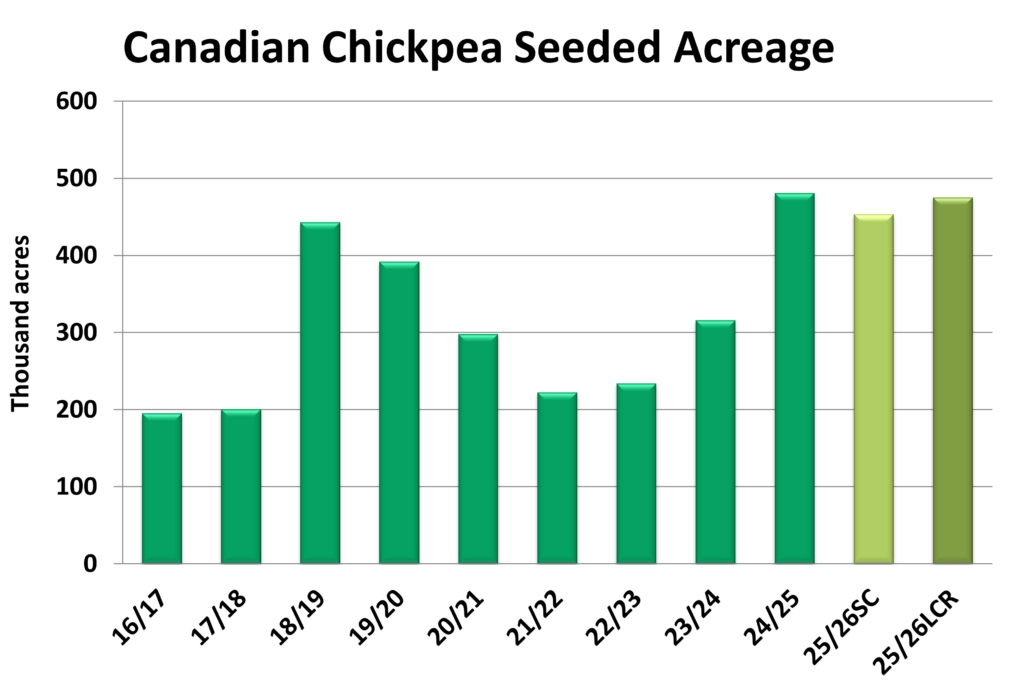

Chickpea acreage tends to be more difficult to forecast. In part, that is because of a smaller survey sample for StatCan but also because word-of-mouth acreage reports tend to be highly variable. The Canadian chickpea market would be hampered by U.S. import tariffs, but price signals for farmers have already been weak for most of 2024/25 and could discourage some acres. Even so, other feedback suggests chickpeas are still one of the better options in core growing areas and could mean very little change in acreage.

StatCan’s survey results are pointing to a 6% drop in chickpea seeded area at 453,000 acres and it is hard to argue too much with that number. Even though that would be a reduction, it would mean acreage is still close to the high end of the last number of years. If so, it raises the potential for heavy supplies again in 2025/26, even if Canadian chickpea exports are unimpeded.

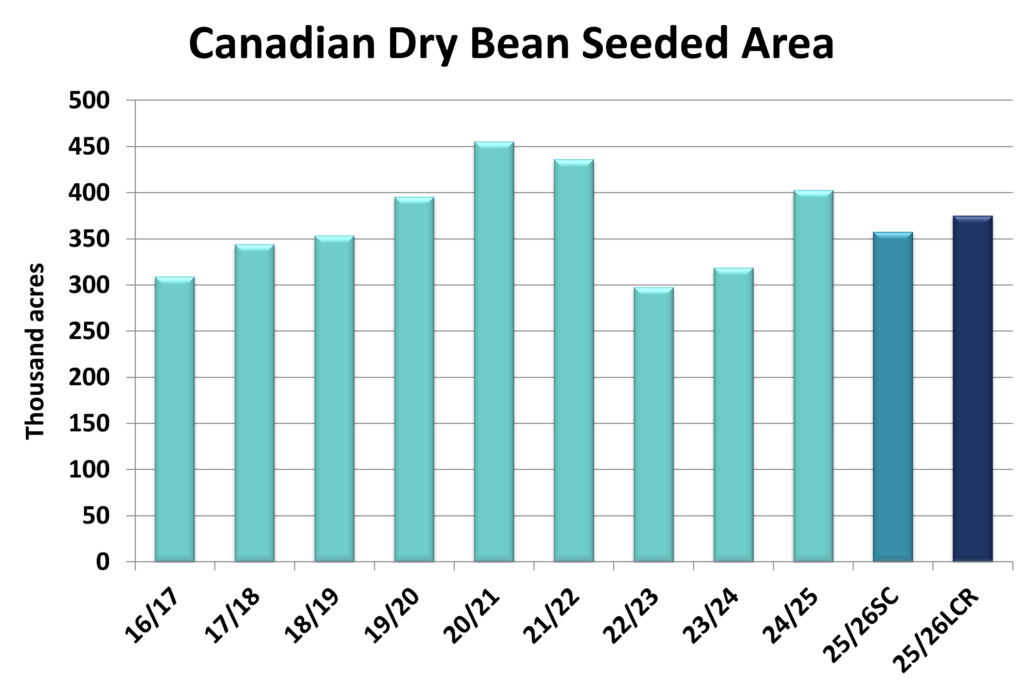

For dry beans, StatCan is estimating seeded area of 357,000 acres, 11% less than last year. The Canadian dry bean market would be affected by U.S. tariffs as it is Canada’s largest destination but so far, bids in Western Canada have not shown much response. Dry bean acreage is largely determined by contracting programs, making it more difficult to nail down the impact of prices on seeded area.

One interesting detail in the StatCan data for dry beans is that seeded area of white types is expected to rise while coloured bean acreage would contract. That would not be too surprising as black and pinto bean acreage returns to more normal levels after last year’s spike in seeded area. One unintended consequence of the trade dispute between the U.S. and Mexico is that it could push more Mexican bean demand toward Canada. The bottom line though is that Canadian dry bean exports could face significant challenges in 2025/26, overshadowing the acreage and supply situation.