Description & Adaptation

Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) has two major commercial classes or seed types that are grown in Saskatchewan: Desi and Kabuli. Desi-type has smaller, angular seeds with thicker coloured seed coats and coloured flowers. Kabuli types have a larger seed size that is more rounded in shape with a thinner cream-coloured seed coat and white flowers. All seeds have a protruding seed root tip that forms a distinctive “beak”.

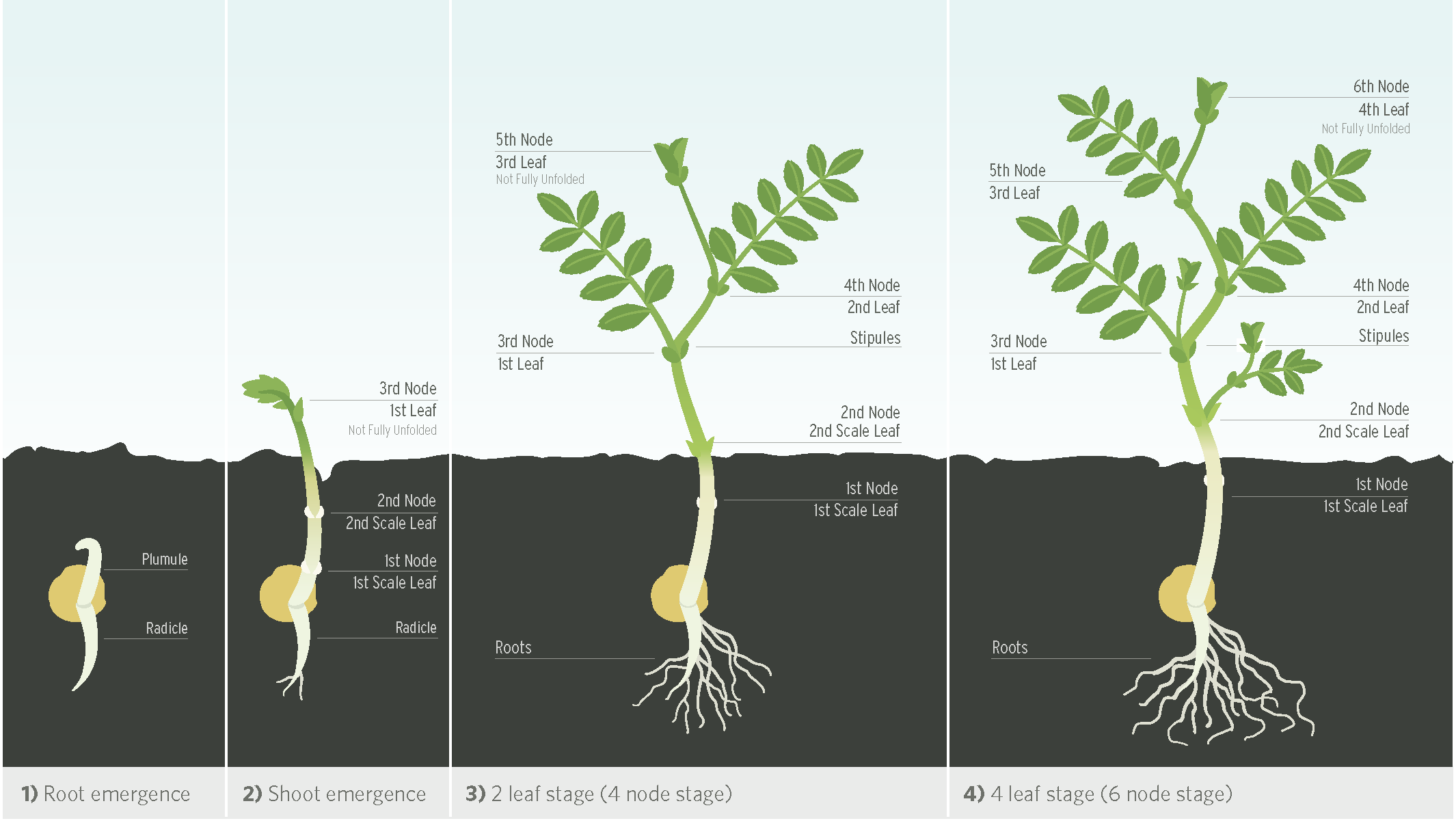

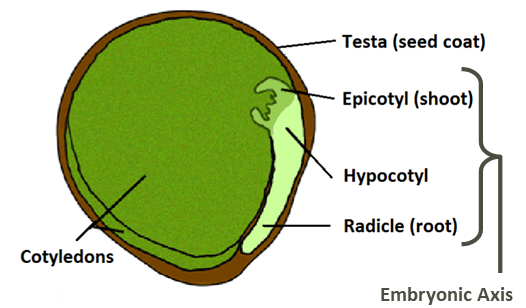

Chickpea seed undergoes hypogeal germination where the cotyledons and seed coat remain below ground. The first two nodes produce scale leaves and at least one node will remain below ground during early growth. This offers protection from late spring frosts and the plant may regrow from these nodes if top growth is damaged. The first true leaf is produced at the third node position. On average, a new node is produced every three to four days.

Desi chickpeas and newer Kabuli varieties have leaves about 5 cm long with nine to 15 leaflets and are described as having a fern-leaf structure. Some older Kabuli varieties, such as CDC Xena, have a single (unifoliate) leaf structure instead of leaflets.

Plants range in height from 30 centimetres (cm) to 70 cm (12 to 28 inches). The plants are erect with natural resistance to lodging. The shatter-resistant pods are short and inflated and contain one to two seeds. The bushel weight of chickpeas is 60 pounds.

Chickpeas have an indeterminate growth habit. Plants continue to flower until they encounter some form of stress, such as drought, heat, frost, or nitrogen deficiency. Highly self-pollinating flowers are produced at the 13 to 14-node stage (usually 50 to 55 days after seeding) in axillary racemes. Cross-pollination is rare, with only 0-1% of cases reported. In most years the plant would be expected to reach maturity in 110 to 130 days.

Adaptation

Chickpeas are heat tolerant and thrive under good moisture conditions with daytime temperatures between 21°C and 29°C, and nighttime temperatures between 18°C and 21°C. However, temperatures of 30°C and higher cause stress during early flowering and pod development. It is relatively drought tolerant as its long taproot (often greater than a metre in depth) can access water from a greater depth than other pulse crops.

Chickpeas grow best on well-drained soils with lighter soil texture, neutral pH, and about 15 to 25 cm (5.9 to 9.8 inches) of growing season rainfall. It is best adapted to the Brown and Dark Brown soil zones in Saskatchewan. Chickpeas are not well adapted to saline soils or to high-moisture areas. They are also not well suited to soils with high clay content or areas where the soil is slow to warm in the spring. Chickpeas do not tolerate wet or waterlogged soils.

Two serious production limitations in Saskatchewan are the long growing season requirement for current varieties and the high risk of Ascochyta blight, an extremely aggressive disease. Planting chickpeas outside the areas of best adaptation has proven to be very risky due to delayed maturity, high green seed content, and destructive disease infections.

Chickpeas can be planted on either summer fallow or stubble in the Brown Soil Zone and on stubble in the Dark Brown Soil Zone. Planting on stubble fields tends to reduce vegetative growth and results in moisture stress to hasten maturity. Due to the indeterminate growth habit of chickpeas, plants can regrow late in the season after rain showers or in the absence of a killing frost.

Desi chickpeas are similar in height and earlier in maturity than Kabuli-type chickpeas. They are more resistant to mechanical, frost, and insect damage and are slightly more resistant to Ascochyta than Kabuli-type chickpeas. Their area of adaptation can extend into the moist Dark Brown soil zone if grown on stubble or lighter textured soils.

Kabuli chickpea varieties are strongly indeterminate, usually maturing in 110 to 120 days. In a cool, wet season, the maturity of Kabulis can easily extend past 120 days. The Brown soil zone provides the conditions most likely to encourage maturity in a reasonable time. Frost in the fall usually causes more damage to Kabulis and increases the level of green seed.

Related Resources

Varieties

Yield is an obvious consideration within a market class. However, other characteristics such as disease tolerance, maturity, or harvestability can quickly overshadow potential yield gains if the plant is limited in reaching its full potential.

Most of the current varieties have improved resistance to Ascochyta blight. Continued breeding efforts are underway to increase the levels of resistance to Ascochyta blight, decrease days to maturity, and improve seed quality.

Want to see how different varieties compare?

Visit the Interactive SaskSeed Guide for information on all chickpea varieties available to Saskatchewan producers.

Related Resources

Exciting Future Ahead for Pulse Breeding

Understanding Protein in Pulses

Pulse Variety Hub

Designed to share the comprehensive, complete results of SPG’s regional variety trials in a format…

Seeding

Chickpeas fit well into a direct seeding crop system under both minimum and no-till soil management. Chickpeas prefer well-drained land or soil with a lighter texture. Research at Swift Current from 1996 to 1998 and in the year 2000 determined that seeding into tall (25 to 36 cm, 9.8 to 14 inches) standing stubble increased chickpea yields by 9% as compared to short (15 to 18 cm, 5.9 to 7 inches) standing stubble. Pod height was also increased with tall stubble.

The use of high-quality seed is extremely important for successful chickpea production. It is important to have seed tested by a seed-testing laboratory for germination, purity, and seed-borne disease. Contamination from seed-borne diseases should be as low as possible. Seed-borne Ascochyta easily transmits to seedlings in the field and only seed with close to zero percent seed-borne Ascochyta should be used.

Application of certain herbicides before harvest can also affect seed germination and/or vigour. Seed from fields treated with pre-harvest glyphosate should be avoided.

Table 1. Guidelines For Tolerances of Seed-Borne Diseases in Chickpea Planted Seed

(These are guidelines only and should be considered along with farming practices and the level of disease risk for the situation)

| Disease (Pathogen) | Tolerance & Factors Affecting the Level |

|---|---|

|

Ascochyta (Ascochyta rabiei) |

The level of infection in the seed as it is ready to go in the ground (after cleaning and application of any seed treatment) must be less than or equal to 0.3% for insurance purposes. Even though a seed test may indicate 0% infection, the seedlot may still contain infected seed and seed treatment is recommended and a pythium controlling treatment is required for insurance purposes. |

| Seed Rots and Damping-off |

These are soil-borne diseases and are not tested for at seed testing labs. The use of seed treatment is strongly recommended for Kabuli varieties. |

| Seed Rots and Seedling Blights |

Sclerotinia, Rhizoctonia, and Fusarium are primarily soil-borne. Botrytis and Fusarium are also often seed-borne and can be tested for at seed testing labs. Up to 10% infection (Sclerotinia and Botrytis) may be tolerable but will result in significant seedling blight if a seed treatment is not used. |

- New seed treatments are continually being registered. Contact the Ag Knowledge Centre at 1-866-457-2377, your local agri- retailer, or an industry representative for updated information on seed treatments registered in pulses. Always refer to the product label before applying the product to the seed.

- The level of seed-borne infection is not the only factor to consider on whether to apply a seed treatment, as most seed treatments are also effective against soil-borne pathogens. Refer to the product label for details.

- Saskatchewan Crop Insurance Corporation (SCIC) may not support claims for loss due to Ascochyta that are made on chickpea fields that had over 0.3% seed infection and/or no seed treatment was used. Refer to the SCIC website for more information.

Source: Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture (SMA)

Seed Treatment

Seed-to-seedling transmission of Ascochyta blight is high in chickpeas and seed treatment is recommended.

In the Brown and Dark Brown soil zones, seed testing zero to 0.2% Ascochyta infection is suitable for planting, but all seed should be treated with fungicide-controlling Ascochyta as even a 0% result may contain some infected seeds at a lower frequency than what was detectable by the lab. Kabuli varieties, with their thinner seed coats, should always be treated for seed/seedling diseases and seed-borne Ascochyta. Desi chickpeas, which have a thick seed coat and tannins in the seed coat, do not usually require a seed treatment to protect them from Pythium, although it too is susceptible to other seed and seedling rots and blights.

Seed treatments for the control of insect pests in chickpeas is much more limited. Currently, registered products include active ingredients of imidacloprid, thiamethoxam, and chlorantraniliprole for use on chickpeas for wireworm, cutworm, and pea leaf weevil control.

Certain fungicides and insecticides may be harmful to inoculants. Check the label of both the inoculant and the seed treatment to ensure compatibility. For optimum results, seed treated with a fungicide should be dried before applying nitrogen-fixing inoculant. Once inoculated, plant as soon as possible, as delays can reduce the seed efficacy of the inoculant. The use of granular inoculant will avoid any problems with direct contact between seed treatment and inoculant.

Related Resources

Chickpea Seed Treatment Options

Pre-Seed and Pre-Emergent Herbicide Options for Pulse Crops

Calculating Seeding Rates

Seeding Tips For Pulse Crops

Tips for Rolling Your Pulse and Soybean Crops

Inoculation & Fertility

Chickpeas can fix 60–80% of their nitrogen requirements through nitrogen fixation. Kabuli chickpeas are excellent nodulators and nitrogen fixers. Desi chickpeas are good nitrogen fixers under ideal conditions but maybe a little sensitive to adverse environmental conditions.

Chickpeas require a specific Rhizobium species for nitrogen fixation (Mesorhizobium cicero), and it is different from Rhizobium used for peas and lentils. Examine the label of any inoculant to make sure that it is appropriate for chickpeas. Some chickpea inoculants will be labelled as “garbanzo bean,” and are appropriate for use in chickpeas. Note that many different strains of this Rhizobium species occur and vary in terms of their effectiveness. The manufacturer may have one or more strains in the inoculant.

Nitrogen fixation is a symbiotic relationship. Rhizobium enters the root hairs of the plant and induces nodule formation. The plant provides energy for the Rhizobium, and the Rhizobium in return converts atmospheric nitrogen from the soil air surrounding the roots into a form that can be used by the plant. Maximum benefit is derived if the supply of available soil nitrogen is low, and the soil moisture and temperature levels are adequate for normal seedling development from the time of seeding until seedlings are well established.

Rhizobium bacteria (either on the seed or in the package) die if they are exposed to stress such as temperature extremes, drying out, or direct sunlight. Inoculant must be stored in a cool, dark place before use and must be used before the expiry date. Following the application of the inoculant, plant the inoculated seed into moist soil as soon as possible.

Inoculants are sensitive to granular fertilizers. Banding fertilizer to the side and/or below the seed is recommended. Never tank mix inoculant with fertilizer. Inoculants are also sensitive to some seed-applied fungicides. Check the label of both the inoculant and seed treatment for compatibility. When using a combination of fungicide and inoculant, apply the fungicide to the seed first, allow it to dry, and apply the inoculant immediately before seeding. Granular inoculants are less affected by adverse environments and seed-applied fungicides than other forms of inoculants.

Inoculants are available in different formulations: liquid, peat-based, and granular. All inoculant formulations will perform equally well if the inoculant is properly applied and if environmental conditions are ideal. Under adverse conditions the best-performing formulation should be granular, followed by peat, and then liquid.

Research completed at the University of Saskatchewan evaluated the performance of inoculant formulations in chickpeas. Results indicated that inoculation using granular formulations was as good as, or better than other formulations. The peat-based and liquid formulations performed as well as the granular formulation in some instances, especially when soil moisture was not limited. Studies carried out in drier soil conditions favoured granular products.

Chickpea crops should be inoculated each time they are grown to ensure enough of the correct strain of highly effective rhizobia is available. Inoculant is economical relative to its potential benefits. The risk of poor nodulation is too great to not inoculate each time the crop is seeded.

Checking Nodulation

The effectiveness of inoculation can be checked by examining the crop at early flowering. It may take up to four weeks after seed germination before nodulation reaches a point where it can be evaluated. The best way to check for nodulation is to dig a plant and gently remove the soil from the roots by washing it in a bucket of water. Nodules are fragile and readily pull off if the roots are pulled out of the soil.

If a nodulation failure is noted by early summer, nitrogen can be applied as a rescue treatment. Check at early flowering, seven to 10 days (approximately the 8-node stage). Nodulation and nitrogen fixation should be well developed by the 12-node stage. Although application rates have not been established, an immediate top-dress application of 44 to 55 kg/ha (39 to 49 lb/ac) should be made.

This nitrogen is best applied as broadcast urea or dribble-banded liquid 28-0-0. The use of a nitrogen stabilizer, such as NBPT, DCD, DMPP, or nitrapyrin, which protects the nitrogen for up to two weeks while waiting for the rain to move the nitrogen into the soil, should be considered with this later application of nitrogen to decrease losses.

Seed-applied inoculant should result in nodules forming on the primary root near the crown. If the inoculant was soil applied (granular), nodules should be found on primary and secondary roots. If nitrogen fixation is active, the nodules will be pink or red on the inside. The lack of nodules indicates rhizobia did not infect the pulse plant. The lack of pink colour (usually green or cream-coloured) indicates the rhizobia is not fixing nitrogen. Nitrogen fixation declines once plants begin pod formation and seed development.

Inoculation for Phosphorus Solubility (for all pulse crops)

Many types of inoculant products contain additional bacteria, fungus, and plant signalling molecules marketed as plant growth promoting rhizobacteria, mycorrhizal fungi, biological growth promoters, and LCO signal molecules. Some of these inoculants can enhance phosphorus solubility and uptake by plants. One such organism would be Penicillium bilaiae, where the fungus colonizes along the root system of the plant, and through the production of organic acids, increases the solubility of soil or fertilizer phosphorus.

Fertility

Fertility requirements for chickpeas are not well-defined. Based on limited data, the requirements for phosphorus, potassium, and sulphur are like peas or lentils. A well-inoculated crop should not require nitrogen fertilizer, provided the appropriate Rhizobium inoculants are used and nitrogen fixation is optimized. Well-nodulated chickpea plants can derive 50–80% of their nitrogen requirement through fixation under favourable growing conditions. If nitrogen fixation is not optimized due to unfavourable growing conditions (e.g., relatively dry seedbed), chickpeas may benefit from low rates of starter nitrogen in some years. Saskatchewan research conducted with four chickpea varieties from 2004 to 2006 showed no differences in seed yield when sown with or without starter nitrogen when granular inoculant was utilized.

Most chickpea varieties are late maturing. Management of maturity is critical to optimize crop quality. In addition to field selection and seeding practices to encourage early crop development, including seeding into standing stubble before May 15, nitrogen fertilization management can be used to manage maturity. Research conducted in Saskatchewan concluded that cropping strategies and practices that produce vigorous early growth allow for an earlier pod set. This early pod set ties up plant resources and minimizes the production of new podding sites. A strong early pod setup provides a strong reproductive sink and helps slow the production of new vegetative tissue. The results showed that nitrogen fertilizer supplied to non-inoculated chickpeas accomplished many of these strategies.

Starter nitrogen (N) of 28 to 56 kg N/ha (25 to 50 lb N/ac), without inoculant, resulted in earlier maturity by an average of 13 days in normal to cooler/wet seasons. In dry years, only marginal differences were noted as drought conditions accelerated crop maturity. Research at Swift Current and Shaunavon, Sask. suggests the best practice may be to apply starter nitrogen instead of inoculating the seed. Earlier research using starter nitrogen for maturity management utilized higher starter-nitrogen rates of 56 to 67 kg N/ha (50 to 60 lb N/ac), applied away from the seed, without inoculants.

Chickpeas have a relatively high requirement for phosphorus. Phosphorus promotes the development of extensive root systems and vigorous seedlings. Encouraging vigorous root growth is an important step in promoting good nodule development. Phosphorus also plays an important role in the nitrogen fixation process and in promoting earlier, more uniform maturity. Chickpeas remove approximately 0.36 lb P205 per bushel of seed.

Chickpeas grown on soils testing low in available phosphorus may respond to phosphate fertilizer even though dramatic yield responses are not always achieved. Even though seed yield may not be increased every year in response to phosphorus fertilizer, the crop may still benefit from earlier maturity.

The maximum safe rate of actual seed-placed phosphate is 20 lb/ac.

Potassium is usually not required as a fertilizer supplement in most soils where chickpeas are grown. When soil test levels are very low, a small amount should be seed-placed. However, seed-placing potassium may cause seedling damage. The maximum safe rate of potassium and phosphorus is 20 lb/ac (22 kg/ha).

If identified as deficient through a soil test, sulphur can be added by side banding, mid-row banding, or broadcasting ammonium sulphate.

Deficiencies have not been consistently identified as a problem in chickpea-growing areas of Western Canada, although no research has been conducted to access the micronutrient requirements of chickpeas. If a micronutrient deficiency is suspected, it is advisable to analyze soil and plant samples within the suspect area and compare the analysis to soil and plant samples collected from a non-affected area of the same field. If the analysis confirms a micronutrient deficiency at a relatively early growth stage, a foliar application of the appropriate micronutrient fertilizer may correct the problem.